The Growing Movement: Tiny Homes as a Homeless Solution

Tiny homes for homeless individuals are an innovative and rapidly expanding approach to America’s profound housing and homelessness crisis. As communities across the nation grapple with a staggering shortage of nearly 7 million affordable housing units for the lowest-income renters, the visibility of unsheltered homelessness has become a defining challenge of our time. In this context, small-scale shelters offer immediate, life-saving relief and a dignified alternative to the precarity of living on the streets, in vehicles, or in crowded congregate shelters.

This movement represents a significant philosophical shift. Instead of merely managing homelessness through temporary mats on a floor, it focuses on providing a foundational asset: a personal, secure space. This approach acknowledges that before an individual can address employment, health, or addiction, they first need a safe, stable place to sleep and store their belongings. These villages are a tangible, scalable response to an emergency that is unfolding on our streets every day.

Key Facts About Tiny Homes for Homeless:

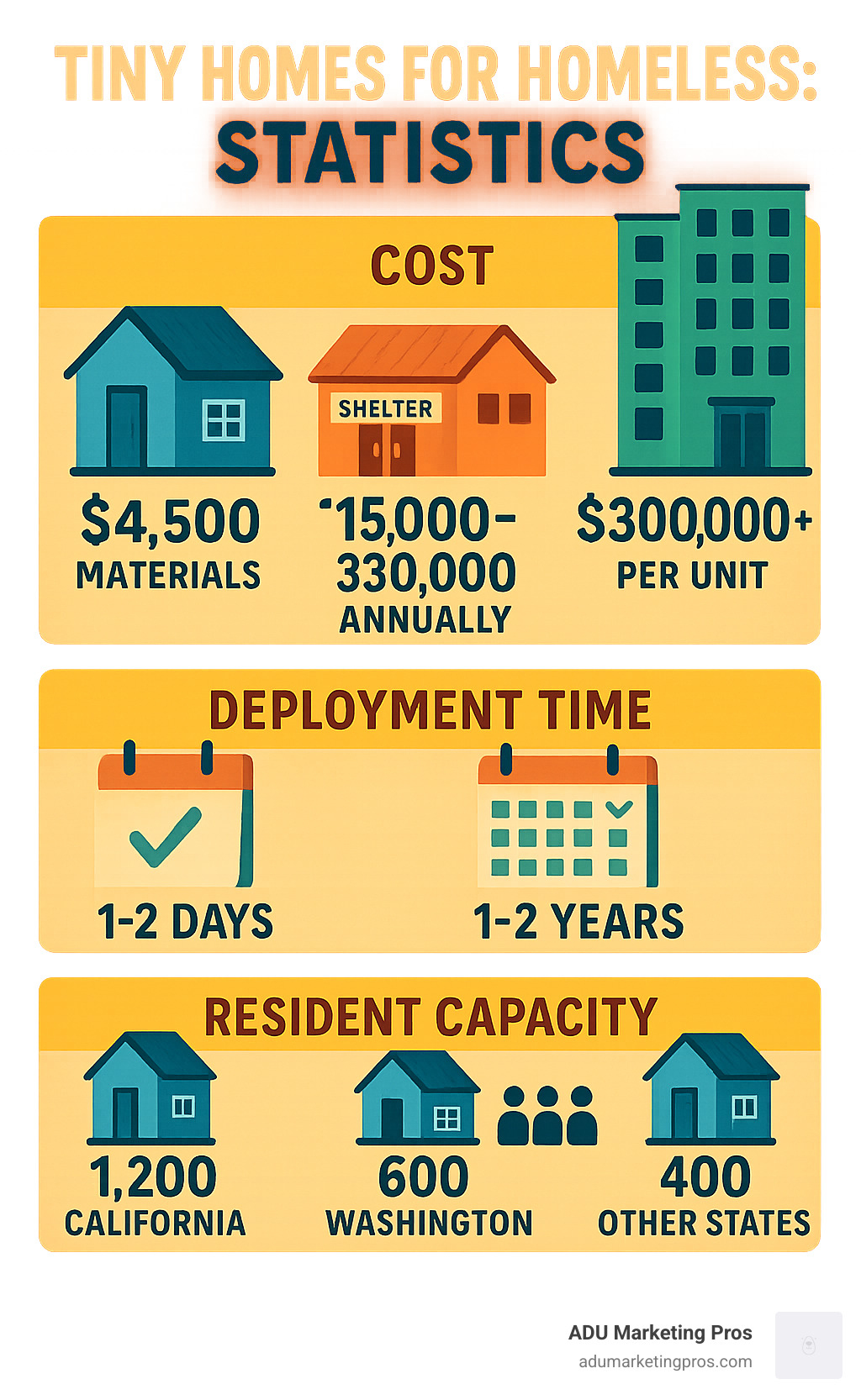

- Cost: While material costs are low at approximately $4,500 per unit, this figure represents only the structure itself. The total cost to establish a village with infrastructure and services is much higher, but still a fraction of traditional construction.

- Size: Typically 64-99 square feet, these units are intentionally small to keep costs low and deployment fast, focusing on providing essential shelter with basic amenities like heat, cooling, and electricity.

- Speed: A single unit can be built in just 1-2 days by volunteer teams, allowing communities to respond to urgent needs with unprecedented speed. Entire villages can become operational in a matter of months, not years.

- Capacity: Villages are scalable, with sites ranging from smaller, 23-bed communities to large-scale operations with over 224 beds, adaptable to the specific needs and available land of a municipality.

- Success: The impact is significant, with programs in Washington State alone successfully moving over 2,000 people from the streets into safe shelter annually, providing them with a platform for rebuilding their lives.

Unlike the multi-year timelines and prohibitive costs of traditional housing development, which can exceed $300,000 per unit, tiny homes offer a different path forward. These are not the lavish, custom tiny houses of television shows, but practical 8×12 foot insulated structures equipped with heating, air conditioning, and, most importantly, a locking door. They provide the three essential pillars for recovery: safety, privacy, and dignity.

From the large-scale deployments in Los Angeles to grassroots efforts in Madison, Wisconsin, communities are discovering that tiny homes serve as highly effective bridge housing. They are faster to build, cost a fraction of permanent construction, and give residents a stable, private base from which to access critical support services. However, the model is not a panacea and comes with its own set of challenges, including significant operational costs and occasional community opposition, which require careful, strategic planning to overcome.

What Are Tiny Homes for the Homeless? A Closer Look

When discussing tiny homes for homeless solutions, it’s essential to make a clear distinction. These are not the aspirational, minimalist dwellings featured in lifestyle magazines. Instead, they are purpose-built structures designed as transitional housing and emergency shelter. Their primary function is to serve as a crucial bridge between the acute dangers of street-level homelessness and the long-term stability of permanent housing. By offering safety, dignity, and a foothold for recovery, they provide the hope and security necessary for individuals to begin rebuilding their lives.

Different Models and Key Features

The adaptability of tiny homes for homeless initiatives is one of their greatest strengths, allowing communities to tailor solutions to local needs, climate, and resources. The models vary widely. Prefabricated Pallet Shelters, made of composite panels, are engineered for rapid assembly and can be erected in under an hour, making them ideal for emergency response. In contrast, the Conestoga Huts used by Occupy Madison in Wisconsin are 99-square-foot insulated wooden structures with a distinctive curved roof, designed for durability in harsh winters. In the Pacific Northwest, the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) has perfected a durable 8′ x 12′ wooden cabin model, often built by local high school students in vocational programs, fostering community involvement.

Despite these variations, a core set of features is remarkably consistent, born from the direct needs of unsheltered individuals. Most units include two beds, a simple but profound design choice that allows couples, family members, or individuals with a caregiver to stay together, preventing the separation often required by traditional shelters. Heating and air conditioning are not luxuries but life-saving necessities, protecting residents from hypothermia or heatstroke. Windows provide essential natural light and a connection to the outdoors, while a small desk and shelving offer a space for personal organization. Above all, every unit has a lockable door. This single feature is consistently cited by residents as the most transformative, restoring a fundamental sense of privacy, security, and control over their personal space that is impossible to achieve on the street.

These structures share some architectural DNA with Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), but their purpose, scale, and legal classification are entirely different. If you’re interested in understanding the nuances between these small housing types, our guide on ADU vs. Tiny House explores these distinctions in comprehensive detail.

Inherent Limitations and Design Considerations

While effective, it’s crucial to be realistic about what tiny homes for homeless can and cannot provide. A significant operational and design limitation is the general reliance on communal facilities. To keep individual unit costs low and construction simple, private kitchens and bathrooms are typically excluded. Instead, residents share centralized buildings with cooking areas, showers, laundry, and restrooms. This model fosters a sense of community and reduces costs, but it also diminishes individual privacy and can create challenges related to cleanliness, scheduling, and safety, which must be managed by on-site staff.

Durability is another key consideration. Materials are often chosen for speed and affordability, which may not be robust enough for long-term, high-use environments. Prefabricated models may have a lifespan of around 10 years, requiring a plan for maintenance and eventual replacement. Furthermore, ensuring full ADA compliance requires thoughtful planning from the outset. Ramps, wider doorways, and accessible bathrooms and showers can add to the cost and complexity, but are essential for serving residents with mobility challenges. The goal is to create spaces that “look and feel like housing,” not like temporary, institutional camps.

To be truly effective and dignified, these projects must integrate the expertise of people with lived experience into every phase of design and operation. As the National Alliance to End Homelessness powerfully emphasizes, their input is not just helpful—it is essential for creating solutions that are practical, respectful, and genuinely meet the needs of those they are intended to serve. For example, resident feedback has led to design changes like placing windows to overlook common areas for a sense of security, rather than facing a fence. You can learn more about this vital principle of involving people with lived experience in design. These limitations don’t negate the value of tiny homes, but they underscore that success requires far more than just four walls and a roof; it demands a thoughtful, human-centered approach.

The Promise of a Small Footprint: Key Benefits

Cities, counties, and non-profits are embracing tiny homes for homeless individuals because they offer a powerful combination that traditional solutions often can’t: immediate, tangible relief combined with the restoration of genuine dignity. They are not just about providing a roof but about creating a safe, stable environment where people can catch their breath, heal from the trauma of homelessness, and begin to build a pathway back to stability.

Cost-Effectiveness and Speed of Deployment

The economics of tiny homes are undeniably compelling, especially when compared to the alternatives. A basic, un-serviced unit can be built with materials costing around $4,500. While the all-in cost per unit in a fully developed village is higher (often $50,000-$85,000 once land, infrastructure, and communal facilities are included), this figure remains a stark contrast to the $300,000, $500,000, or even more required to build a single new apartment unit in many urban centers. This dramatic cost difference allows cities to stretch limited public funds and philanthropic dollars to serve far more people.

The speed of deployment is an equally critical advantage. In a crisis where every night spent on the street is a risk to life and health, the ability to respond quickly is paramount. With organized volunteer teams or efficient prefab construction, a single structure can be erected in a day or less. This capacity for rapid response is a game-changer. The City of Los Angeles demonstrated this scalability by adding over 500 tiny home beds in the first half of 2021 alone—a feat that would be utterly impossible with conventional construction methods.

| Metric | Tiny Home Villages | Traditional Shelters | New Apartment Construction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost Per Bed (Approx.) | $4,500 (materials), but total village costs can be $1M setup + $800k-$900k/year | Significantly cheaper in short-term; $15,000-$30,000 annually | $300,000+ per unit |

| Time to Build/Deploy | Days to weeks | Immediate setup (in existing buildings) | Years |

| Key Features (Privacy) | High (individual, lockable units) | Low (congregate settings) | High (private apartments) |

While the full operational budget for a village is significant—covering 24/7 staffing, security, case management, utilities, and maintenance—the math often still favors tiny homes. When you consider the high cost of emergency services, encampment cleanups, and the long-term social costs of chronic homelessness, providing this form of stable, supportive shelter is a wise public investment.

Restoring Dignity, Safety, and Stability

The true, transformative power of tiny homes for homeless individuals lies in their ability to restore human dignity. A locking door is the most frequently cited feature, providing a sanctuary from the constant fear and hyper-vigilance of street life. This small, personal space—even if only 64 or 100 square feet—allows a person to sleep soundly, store possessions securely, and have a private moment to think, plan, and simply be.

These weatherproof shelters offer life-saving protection from the elements, preventing frostbite in the winter and heatstroke in the summer. Many villages also implement pet-friendly policies, a deeply compassionate and practical measure. For many experiencing homelessness, a pet is a non-judgmental source of emotional support and their only family. Forcing them to abandon that companion to enter a shelter is an impossible choice; pet-friendly tiny homes remove that barrier. Furthermore, the best projects incorporate trauma-informed design, using elements like calming color palettes, ample natural light, and village layouts that balance privacy with community connection to create a healing environment.

Community First! Village in Austin, Texas, is a world-renowned example of how combining safe, permanent housing with a vibrant, supportive community can transform lives. Their sprawling campus proves that these villages can do more than shelter people; they can help residents rediscover purpose, build relationships, and find a true sense of belonging. You can learn more about their groundbreaking approach at Community First! Village’s successful model.

A Stepping Stone to Permanent Housing

The most successful and ethically grounded programs view tiny homes as a crucial bridge, not a final destination. The explicit goal is to provide a short-term, stable environment where residents can focus on moving toward permanent housing. Organizations like Hope the Mission in Los Angeles design their programs with this trajectory in mind, aiming for residents to transition onward within an average of 4 to 6 months.

This transition is only possible because of the comprehensive on-site services that are wrapped around the housing. This is the critical ingredient that turns a collection of small structures into a launchpad for recovery. These services include intensive case management, connections to physical and mental health counseling, substance abuse support, life skills workshops, job training, and dedicated housing navigation to help residents find and secure a permanent home. This robust, wrap-around support system is what makes the model work. The Low Income Housing Institute’s (LIHI) program in Washington State, which serves over 2,000 people annually across its network of villages, demonstrates the effectiveness of this model at scale, reporting high rates of success in helping participants find employment and transition to permanent housing.

For those interested in the broader world of small-scale housing solutions, our guide on Small Houses offers additional insights into design and construction trends.

Navigating the Problems: Challenges of Tiny Home Villages

While tiny homes for homeless individuals offer tremendous promise and have achieved remarkable success in many cities, implementing these solutions is fraught with very real challenges. For any community, non-profit, or municipality considering this path, a clear-eyed understanding of these obstacles is essential for sustainable success.

The “Not In My Backyard” (NIMBY) Phenomenon

Perhaps the single greatest hurdle to developing tiny home villages is community opposition, often referred to as NIMBYism. When a project is proposed, it can trigger fears among nearby residents about declining property values, increased crime, and negative impacts on neighborhood character. These concerns, whether real or perceived, can fuel intense political pressure that can delay projects for months or kill them entirely during the sensitive zoning and permitting process. Most municipal zoning regulations and building codes were written long before tiny home villages were conceived, creating a complex and often contradictory bureaucratic maze for developers to navigate.

Finding a suitable location is a parallel challenge. The path of least resistance often leads to siting villages in remote industrial or commercial zones, far from residential areas. However, this isolation can be deeply detrimental, cutting residents off from public transportation, grocery stores, healthcare facilities, and potential jobs. As the National Alliance to End Homelessness argues, this practice is “impractical, unfair, and unjust.” The most successful projects are those integrated into the fabric of a community. Encouragingly, stories of how some communities overcame neighbor concerns show a common pattern: proactive community engagement, strong leadership, and the eventual realization that a well-managed village is a far better neighbor than a sprawling, unmanaged encampment.

Operational and Financial Realities

While the low material cost per home is an attractive headline, the high operating costs for an entire village are a sobering reality that must be planned for. The initial capital to build a village is only the beginning. For example, a village for 50 people in Madison, Wisconsin, cost approximately $1 million to set up and requires an ongoing annual budget of $800,000 to $900,000 to operate. These substantial costs cover essential infrastructure (sewer, water, power connections), 24/7 staffing for case management, security, and site management, as well as recurring expenses for utilities, insurance, maintenance, and sanitation services.

These ongoing operational expenses highlight the critical need for sustainable, long-term funding commitments from cities, counties, or philanthropic partners. A village cannot succeed if its funding is precarious or limited to a single year. This financial reality is a major reason why successful villages are almost always operated by experienced non-profit service providers who have the expertise to manage complex budgets and blend diverse funding streams.

For those interested in sustainable building practices that can help mitigate some long-term utility costs, our insights on Eco-Friendly Small Homes explore how thoughtful design and materials can improve operational efficiency.

Criticisms and the Risk of Substandard Housing

Even strong supporters of the model acknowledge legitimate criticisms and potential risks. A primary concern, voiced by advocates like Donald Whitehead Jr. of the National Coalition for the Homeless, is that tiny homes are not a permanent solution. They are an excellent emergency and transitional intervention, but they do not replace the fundamental, systemic need for more permanent affordable housing, living-wage jobs, and accessible healthcare.

There is a tangible risk that politicians and the public may view tiny homes as a “panacea,” a quick and visible fix that allows them to sidestep the harder, more expensive work of addressing the root causes of homelessness. The most serious ethical concern is the potential for these villages to create a new form of segregated housing, where people experiencing poverty and homelessness are concentrated and housed separately from the rest of the community, often in conditions that do not meet the standards of permanent housing. To mitigate this risk, it is imperative that tiny homes are officially designated and operated as temporary, transitional housing and that they are implemented as one tool among a comprehensive suite of solutions aimed at creating permanent, integrated, and truly affordable housing for all.

The Blueprint for Success: How to Implement Tiny Homes for Homeless Effectively

Creating a successful tiny homes for homeless community is a complex undertaking that requires far more than just land and construction materials. A successful project weaves together robust community support, comprehensive and compassionate services, and a sustainable financial model to create a genuine stepping stone to stability and permanent housing.

Building a Foundation of Community Support

No project can succeed in the face of determined community opposition. Therefore, successful projects begin with building trust and consensus long before the first shovel hits the ground. This is often achieved through strong public-private partnerships, where a city or county provides the land and funding, while an experienced non-profit service provider manages the day-to-day operations and community relations, as seen in the successful models in Los Angeles and Seattle. Proactive volunteer engagement is also key; involving local residents, schools, and businesses in building or supporting the village can transform potential opponents into dedicated advocates. Furthermore, support from faith-based organizations and high-profile corporate sponsors, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger’s donation to build homes for homeless veterans, provides crucial funding, legitimacy, and a powerful endorsement of the mission.

Operations and On-Site Services

The physical homes are merely the hardware; the on-site services are the essential software that makes the entire system work. The most effective villages function as recovery-oriented communities, not just as shelters. This requires a rich ecosystem of on-site support services, including:

- Intensive case management to help residents create personalized goal plans, navigate bureaucracy, and stay on track.

- Mental health counseling and substance abuse support to address the underlying trauma and health conditions that often accompany or lead to homelessness.

- Job training, resume building, and placement services to help residents build skills and achieve economic stability.

- Connections to healthcare, including mobile medical clinics and assistance signing up for benefits, to manage chronic conditions.

- Dedicated housing navigation to actively search for, apply for, and secure permanent housing placements.

To foster a sense of ownership and empowerment, some villages, like Occupy Madison, utilize self-governance models. In these systems, residents are actively involved in the day-to-day decision-making and management of the village, from setting community rules to organizing chores. This participation builds leadership skills and creates a powerful sense of responsibility and shared community.

Funding and Financial Models for tiny homes for homeless

Sustainability is impossible without a stable and diverse funding strategy. Relying on a single source of income is a recipe for future crisis. Successful projects typically braid together multiple funding streams, including direct city and county funding, private philanthropy from foundations and individuals, corporate donations of both cash and in-kind materials (like lumber or roofing), and competitive federal grants. California’s Homekey Program, for example, has been a game-changer, providing billions in state funds for the acquisition and creation of interim and permanent housing, including tiny home villages. Grassroots fundraising, from bake sales to online campaigns, also plays a powerful role in both raising funds and demonstrating broad community buy-in.

For those in California, understanding the specific construction landscape is key. Our work with Tiny House Builders California shows how local building expertise can be leveraged to serve both market-rate and humanitarian housing needs, creating potential for social enterprise partnerships.

Measuring Long-Term Outcomes and Success

The true metric of success for a tiny home village is not how many units are built, but what happens to the people who live in them. To prove their effectiveness and justify ongoing investment, programs must rigorously track and report their outcomes. Success should be measured by:

- Transition rates to permanent housing: This is the single most important scorecard for any interim housing program.

- Health and wellness improvements: As a 2019 study on the health conditions of unsheltered adults demonstrates, moving from the street into a stable shelter dramatically improves physical and mental health outcomes. Tracking these changes is crucial.

- Employment rates and income growth: Stable housing is a prerequisite for finding and keeping a job. Measuring residents’ progress toward economic self-sufficiency is a key indicator of success.

- Community integration and reduced recidivism: The ultimate goal is to serve as a bridge back to the wider community. Success means residents not only move to permanent housing but stay there, avoiding a return to homelessness.

Case Studies: Tiny Home Communities in Southern California and Beyond

Theory is valuable, but real-world examples reveal the true potential and practical challenges of using tiny homes for homeless individuals. From the massive, rapid deployments in major American cities to smaller, community-driven villages, innovation is happening across the country, offering a rich tapestry of models to learn from.

Los Angeles: A City Embracing the Model

In the face of a severe homelessness crisis, Los Angeles County has become a national leader in scaling the tiny home village model as a form of interim housing. Sparked by the success of Hope the Mission’s first village in North Hollywood in early 2021, the city and county embarked on a rapid expansion, adding over 500 beds in just the first six months. The largest of these, the Arroyo Seco Village in Highland Park, was funded and built by the City of Los Angeles and features 117 units and 224 beds. The LA model is characterized by its speed, scale, and clear focus: these villages are designated as interim housing with comprehensive support services, with the explicit goal of transitioning residents to permanent housing within four to six months. While the city has proven it can build these sites quickly, it now faces the ongoing challenge of securing sufficient operational funding and ensuring a steady flow of permanent housing options for residents to move into.

Innovative Models Across the Nation

While Los Angeles demonstrates scale, other communities have pioneered different and equally influential approaches.

- Community First! Village (Austin, Texas): Perhaps the most famous and ambitious project in the country, Community First! is not interim shelter but a 51-acre master-planned community that provides affordable, permanent housing for more than 350 formerly chronically homeless individuals. It offers not just homes (a mix of tiny homes and RVs) but a profound sense of belonging, with on-site medical services, an organic farm, a cinema, art studios, and micro-enterprise opportunities that allow residents to earn a dignified income. It is a model of holistic, relational care.

- Occupy Madison (Madison, Wisconsin): This project grew out of grassroots activism and embodies a spirit of self-determination. The village is cooperatively owned and operated by its residents, who participate in a democratic self-governance model. They build their own 99-square-foot homes in a shared workshop, fostering skills and a deep sense of ownership. It is a powerful example of a small-scale, resident-driven solution.

- Low Income Housing Institute (Seattle, Washington): LIHI has become a leader in the public-private partnership model. Operating 18 villages across the Puget Sound region, they serve over 2,000 people annually. LIHI partners with local communities and faith organizations to secure land and support, while providing professional case management. They have also created villages tailored to specific populations, including a village designed with and for the local American Indian and Alaskan Native community, demonstrating a commitment to culturally competent care.

Finding places in Southern California that allow tiny houses for homeless

For non-profits, faith groups, or developers looking to create tiny homes for homeless communities in Southern California, the regulatory landscape is becoming increasingly favorable. The sheer scale of the homelessness crisis has forced many municipalities to adopt emergency ordinances and zoning reforms to facilitate the creation of shelters. Cities like Chula Vista, San Diego, and others have followed Los Angeles’s lead in streamlining the approval process for interim housing projects.

California’s Homekey Program has been an instrumental state-level intervention, providing billions of dollars to help public entities and non-profits acquire hotels, apartments, and other properties for conversion into housing, and these funds can also be used for new construction projects like tiny home villages. Furthermore, the broader political and social movement to legalize Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) has helped normalize the concept of small-scale housing, which can indirectly ease the path for tiny home shelter projects. To learn more about the specific regulations and opportunities in the region, our guide on Places in Southern California That Allow Tiny Houses provides detailed, actionable information.

Conclusion

Tiny homes for homeless individuals represent far more than just an innovative construction trend; they are powerful symbols of a compassionate, pragmatic, and urgent response to a complex human crisis. From the rapid, large-scale deployments in Los Angeles to the deeply relational, permanent community being built at Community First! Village in Austin, these initiatives have proven their immense value across a diverse range of contexts. They succeed where traditional shelters often fall short by providing the foundational elements of human dignity: a private space, a locking door, and a safe place to rest and heal.

However, their success is never guaranteed by construction alone. As we have seen, the most impactful and sustainable tiny home villages are those that are wrapped in comprehensive, person-centered support services—including intensive case management, mental and physical healthcare, and pathways to employment. They must be understood and operated as stepping stones, not as final destinations. To do so requires acknowledging and overcoming the very real challenges of community opposition (NIMBYism) and the significant, ongoing operational costs, which demand thoughtful community engagement and sustainable, long-term funding commitments.

Ultimately, tiny homes for homeless individuals are most effective and ethical when they are implemented as one critical component of a much broader, system-wide strategy. They are a powerful tool for providing immediate safety and dignity, creating a vital bridge from the street to stability that can, without exaggeration, save lives. But they cannot replace the urgent need to build more permanent affordable housing, address income inequality, and reform the systems that allow homelessness to persist. For those in the construction, design, and real estate industries, this movement is a profound opportunity to contribute to one of the most pressing social challenges of our time. At ADU Marketing Pros, we believe in the power of innovative housing to transform lives, and by understanding the full landscape of these solutions, we can all help build not just houses, but hope.